About Mary Austin

I plan to write about an American writer, Mary Austin, who is unknown in Japan, including my experience of meeting her. In my writing I will explore who she was: what she was thinking, how she was living, where she would go to do her writing. I will read various texts about her and her writings in books and on the web as I write the article. Kazue Daikoku(editor)

Photo above: Charles F. Lummis*

*Her best known work "The Land of Little Rain" is available with drawings by Yukari Miyagi. (started in July 2008)

#0 How I Met Mary

For me, the first meeting with Mary was three or four years ago. It was a time when I was reading and translating Terry Williams's(b. 1955 - ) works. Terry is a writer and a naturalist who writes about the American desert, and she lives in Utah. I was lured to desert literature and naturalists in America by Terry. I read "Desert Solitaire" written by Edward Abbey (b. 1927- d. 1989), which was published in Japan.

I found Mary Austin's name in the reference to Terry Williams at amazon.com when I was looking for her new work. Terry wrote the introduction of Mary's "The Land of Little Rain"(1903) which was the most well-known of her works. Then Mary's book came to me, and her books continued being delivered to my place one by one. I received the sixth book, "The American Rhythm" last month. It is one of the original resources for making this poetry anthology "The Deer-Star - Amerindian Songs -".

I noticed immediately that "The Land of little Rain", which was the first book of hers for me, was a great book. After reading the first several lines, I was deeply moved by it. Dry, sharp and passionate writing drew landscapes of the desert and nature. I passionately wanted to translate it into Japanese, but the English texts were difficult for me, and it seemed to me very hard to translate it at that time. Thus I planned to translate Mary's another book "The Basket Woman (A Book of Indian Tales)" into Japanese first, to know her writing style and desert things. The book is a collection of short stories for children. I began to translate it with Jeff Brower who is a member of Happa-no-Kofu, and published it when we started our Happa-no-Kofu website in April 2000. We added one or two stories every month and finished the series one year and three months later. The translation was very hard for me, because even though the book was for children, Mary wrote in a noble and literary style. I felt much admiration for her at this point. My co-translator, Jeff(Montreal) helped me to complete this work, as he has a good knowledge of the desert and American Indians, and also is able to interpret the stories very well.

My interest and respect for her have increased and expanded on and on as I read more and know her better. I was surprised and impressed that her thoughts and feeling could move me so deeply even though she lived one hundred years ago.

#1 Mary And Wallace

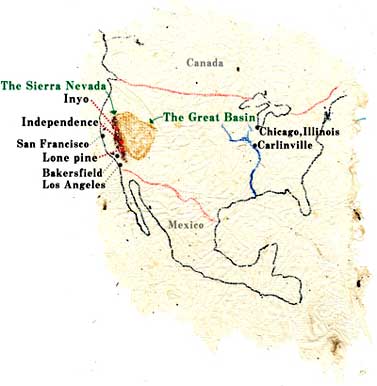

Mary Hunter was born in 1868 in Carlinville, Illinois. After she graduated from college in 1888, her family moved to Bakersfield, California. When she was tutoring children on a ranch near Bakersfield, she met Stafford Wallace Austin, who lived on a neighboring ranch. They met in 1890 and had a hasty marriage in 1891 and then moved to San Francisco. Wallace(as Mary called him) was born and grew up in Hawaii. His parents were owners of a sugar plantation. When he was twenty, his family moved to the Bay Area of California, and he graduated from UC Berkeley and completed his education there.

Mary and Wallace lived in San Francisco for a while, and then lived in various towns in the Owens Valley, California, and arrived in Lone Pine at last in 1892. Wallace intended to develop irrigation systems and failed. He worked various odd jobs. Then he began to teach at school for a while, and he was appointed Inyo County Superintendent of Schools in 1898. In 1900 the couple built the house which they designed, in Independence.

Mary and Wallace fought a battle against the City of Los Angeles water plans in 1905. And that was the year when they divorced. At that time Mary was thirty-seven, Wallace was forty-five, and their daughter Ruth was about eleven.

#2 Her Interests In Nature

She was thinking of being a writer before she was ten, and actually she began to write in her early years. She was also interested in nature and developed it. As she encountered a few books about geology and was inspired by them, she began to collect fossils. Since she lived in the San Joaquin Valley where her parents had their own homestead, she was fascinated by the country and spent a large part of her time out-of-doors from morning until night. Nature and the life of the country became the object of her interest: to see the habits of the night-prowling animals, to record the kinds of growing things, how the seasons flow, the movements of sheep, the stories of herders, and stories of Indians and pioneers. She made frequent visits to the owner of Tejon Rancho to obtain his knowledge of the land, and he was glad to pass on it to the quick and intelligent girl.

Her first publication, The Land of Little Rain, is a nonfiction book which is about the California desert country and the people who lived there. She completed it only in a month, but it may not be strange as she said, "I was only a month writing ... but I spent twelve years peeking and prying before I began it."

Photographer of Mary's portrait:

*Charles Fletcher Lummis (1859-1928): southwestern author, librarian, editor, historian, archeologist and activist on behalf of historic preservation.

#3 How Mary came to know the Indians

<From her autobiography "Earth Horizon">

That winter, when she lay sick in bed day after day with no help but the uncertain visits of Indian women, she grew gradually aware, by the way the child throve, that the mahala was nursing it along with her own beady-eyed, brown dumpling. Mary roused herself sufficiently to have the Doctor see the Paiute woman to make sure that they ran no danger, and for the rest, since the mahala was shy about her service, accepted it gratefully in silence. Two or three years later, because Mary's child was not talking as early as it should, that mahala came all the way to Lone Pine to bring her dried meadowlarks' tongues, which make the speech nimble and quick.

It was in experiences such as this that Mary began genuinely to know Indians. There was a small campody up George's Creek, brown wickiups in the chaparral like wasps' nests. Mary would see the women moving across the mesa on pleasant days, digging wild hyacinth roots, seed-gathering, and, as her strength permitted, would often join them, absorbing women's lore, plants good to be eaten or for medicine, learning to make snares of long, strong hair for the quail, how with one hand to flip trout, heavy with spawn, out from under the soddy banks of summer runnels, how and when to gather willows and cedar roots for basket-making. It was in this fashion that she began to learn that to get at the meaning of work you must make all its motions, both of body and mind. It was one of the activities which has had continuing force throughout her life.

#4 Trout Fishing

<From "Earth Horizon">